Drawing from observation, students will sketch a paper ball using contour and shading techniques. Recommended for 5th Graders.

Form: 3-dimensional (height, width and depth) figure that encloses volume.

Shape: a 2-dimensional (height and width) figure created with joined lines.

Value (Hue/Shade/Tint): a measure of relative lightness and darkness. In this lesson light and shadowed areas create the illusion of depth which makes the object appear more realistic.

Proportion: the relationship between the parts of a single object to its whole. In this lesson it’s the parts of the paper ball compared to the whole ball.

Hatch Marks: using short lines, close together to make an area darker.

Observation: the action of carefully noticing things. In this lesson students will draw what they see.

• Pencils, erasers (1 per student)

• Clip boards, (1 per student, optional)

“Drawing from observation” means looking at real 3-dimensional objects and using the illusion of depth (the missing 3rd dimension) to turn those forms into 2-dimensional shapes. When drawing from observation, the artist records visual information as it’s seen and expresses creativity by choosing which details to include, exaggerate, or leave out. This method of drawing depends on the artist’s ability to copy what is actually seen.

Drawing from observation became more important during the Renaissance, as European artists and scientists became interested in observing and recording objects and people in the world in order to understand them. Learn more about drawing HERE.

This activity is critical in bringing students to a more advanced level of drawing. Children naturally draw symbolically – for example, by drawing smiley faces instead or realistic faces. A ball of paper can't be reduced to a symbol; therefore, students can’t easily default to a more natural way of drawing it, and must rise to the challenge of drawing what they actually see. There will be a learning curve, it won’t come easily. Remind them of how hard it was to learn how to hold their breath under water when learning to swim, or how to write the alphabet when first learning to write. It improves with practice. Find out who the best drawer is in the class and ask them if they practice. They usually say yes.

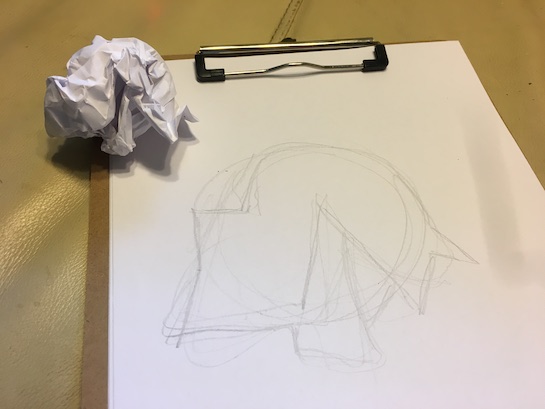

For this activity, each student will need three to four sheets of copy paper and a pencil. If clipboards are used, a stack of paper can be set up on each clip-board ahead of time.

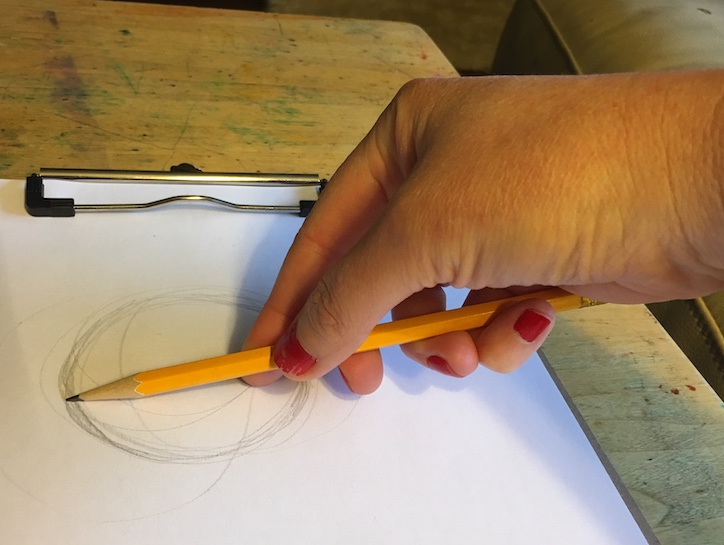

The Art Docent will be drawing in front of the students for this activity. Some practice in advance is recommended. Such drawing can either be done on large paper, or on a white board or active board.

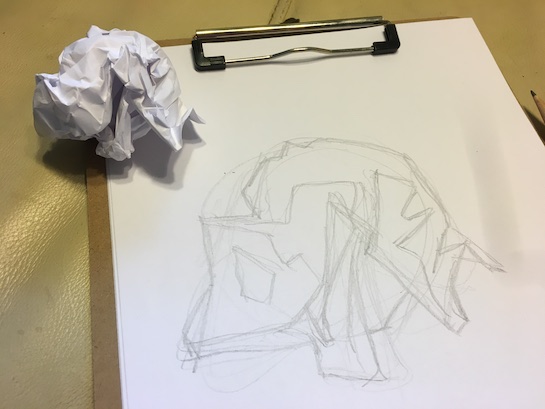

The goal of this activity is to have students consciously move from drawing symbolically (i.e. happy faces, stick figures) to drawing with more realism. “Draw what you see!” Success shouldn’t be measured by how perfect the results are, but by the effort that a student puts into following the steps. Stepping out of your ‘comfort zone’ is required to make the leap from childhood drawing techniques to adult drawing techniques. Adult drawers engage in quite a bit of trial and error.

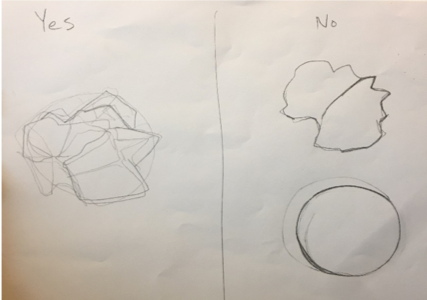

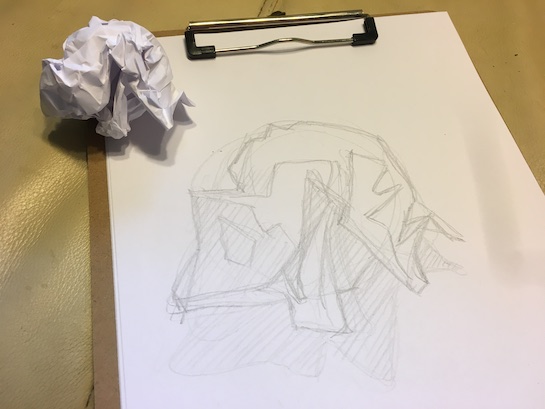

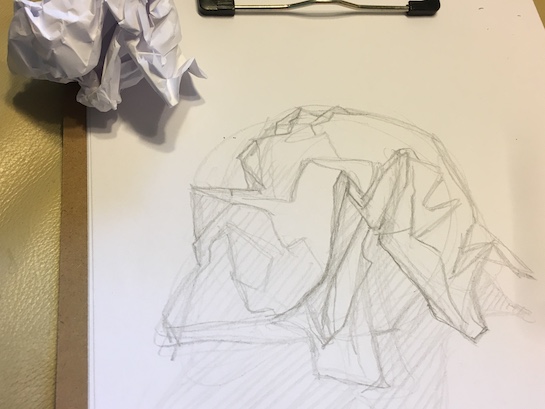

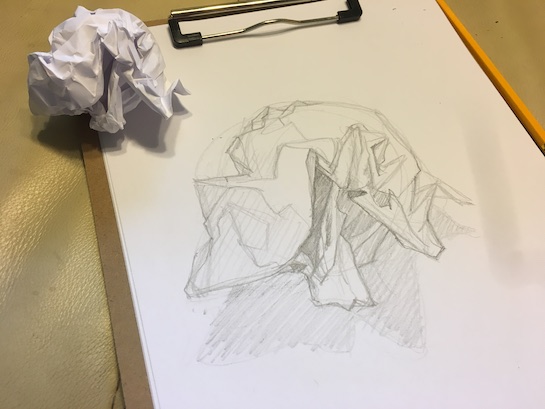

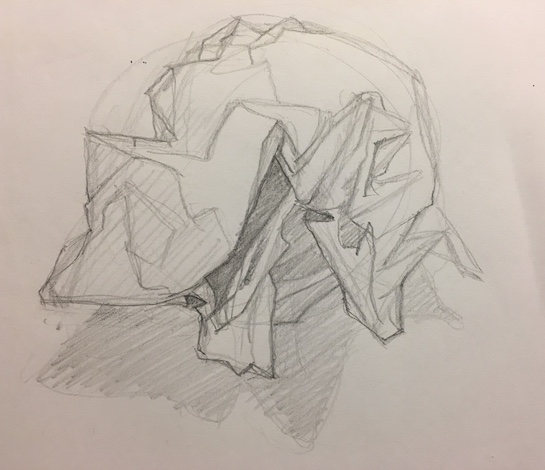

Here are examples of successful and unsuccessful observational drawings:

The drawing on the left appears messy, but the extra lines indicate that the student is searching for the correct shapes, including shapes within other shapes. This student has left the “mistakes” visible, which shows that he/she isn't letting perfectionism keep the artist from finding the “correct“ lines. This accomplishes the goal of the lesson.

On the right, the student drew what they think they saw (not truly observing) and is stuck erasing and redrawing lines. The drawings don’t show much exploration because of the fear of making mistakes. This student may benefit by starting over.

Post the vocabulary words on the board and explain them carefully. Refer to them often during the lesson.

Each student should have several sheets of white unlined paper and a pencil. The paper can also be on a clipboard and they can sit where ever. Don’t allow them to work on a group drawing or to sit with friends who want to talk. Discourage talking: “You can’t draw and talk at the same time!”

Drawings by Michelle Clay. Special thanks to Nicholas Palermo at the Rhode Island School of Design. YouTube: Basics #60-Anyone can draw from observations with these steps (charcoal drawing).

21st Century Thinking Skills

Thinking flexibly, persisting, creating, innovating, listening with empathy, taking responsible risks, reflecting, observing, making connections, visualizing, sequencing, comparing/contrasting, determining main idea, finding evidence, problem solving, determining point of view, cause and effect, fact and opinion, decision making, analyzing, evaluating.

WA State Learning Standards

(VA:Cr1.2.5) a. Identify and demonstrate diverse methods of artistic investigation to choose an approach for beginning a work of art.

(VA:Cr2.1.5) a. Experiment and develop skills in multiple art-making techniques and approaches through practice.

(VA:Cr2.2.5) a. Demonstrate quality craftsmanship through care for and use of materials, tools, and equipment.

(VA:Cr2.3.5) a. Identify, describe, and visually document places and/or objects of personal significance.

(VA:Re7.1.5) a. Compare one's own interpretation of a work of art with the interpretation of others.

(VA:Re8.1.5) a. Interpret art by analyzing characteristics of form and structure, contextual information, subject matter, visual elements, and use of media to identify ideas and mood conveyed.

(VA:Cn10.1.5) a. Apply formal and conceptual vocabularies of art and design to view surroundings in new ways through art-making.

Arts Integration Opportunities

Science: Record visual and factual date in journals when studying plants, trees, rocks etc.

Language Arts: Describe how perseverance helped the student overcome a new challenge and become proficient in a new skill.

Spelling: the vocabulary words.

Please note: These lesson plans are intended for non-profit use only. Use of these plans for commercial purposes should give attribution to the Issaquah Schools Foundation and be accompanied by a nominal donation at www.isfdn.org/donate. Thank you.

Fueling Success for Every Student, Every School